Bringing in DevOps to an organization means making some changes to the culture and structure of teams and the organization. These changes are often disruptive and frequently meet with some resistance from leadership, teams, and individuals.

A successful DevOps team is cross-functional, with members that represent the business, development, quality assurance, operations, and anyone else involved in delivering the software. Ideally, team members have shared goals and values, collaborate continuously, and have unified processes and tooling. They are responsible for the entire lifecycle of the product, from gathering requirements, to building and testing the software, to delivering it into production, and monitoring and maintaining the software in production.

But defining the correct organizational structure is a little more difficult than explaining the role and makeup of the team. There are a lot of different ways to position DevOps within the organization, and what works in one environment doesn’t always fit the needs or culture of another.

Conway’s Law

In order to allow a team to work in a truly collaborative fashion, the organization has to align their goals. And that usually means aligning the organizational structure with the desired team structure, as observed by the proverb known as Conway’s Law.

“organizations which design systems … are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations”

– Melvin Conway

If you really want teams to be able to have shared responsibilities, they need to have common goals. And the only way to share common goals is to make sure that they report to the same people and are measured on collective successes.

This idea isn’t new to DevOps. In the 1980’s, Jack Welsh, at the time the CEO of General Electric, introduced the idea of the “boundaryless organization” in a process that became known as GE Work-out. The focus was teams that were able to quickly make informed decisions, what people in Agile might today call self-organizing teams.

Anti-Patterns

Perhaps it is easiest to start with some examples of anti-patterns- structures that are almost always doomed to fail. Well, doomed to fail is too strong. These organizational structures bring with them some significant hurdles to success.

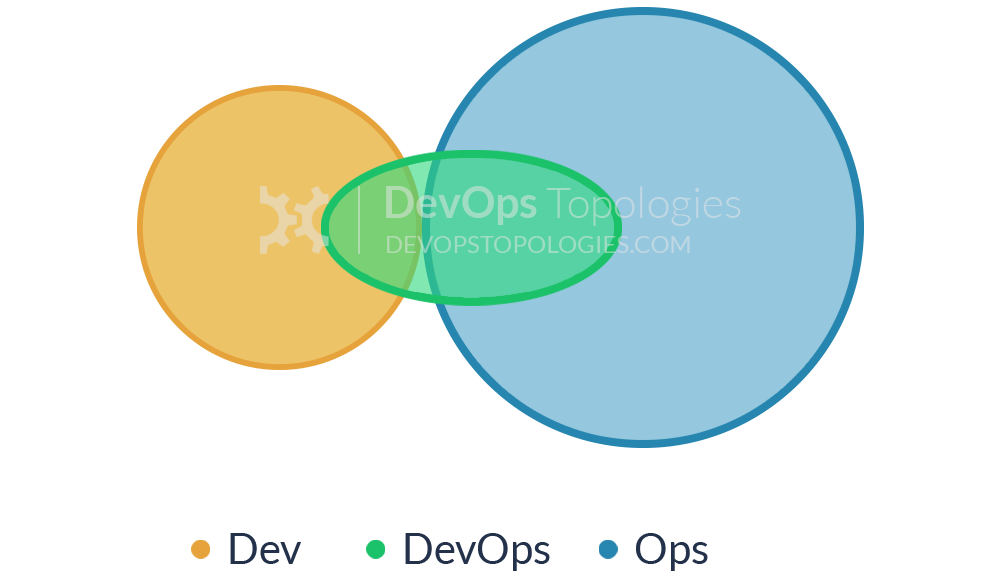

In each of these, I show Dev and Ops as the involved parties, but other groups like QA are affected in the same way. All images from Matthew Skelton, http://web.devopstopologies.com/, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

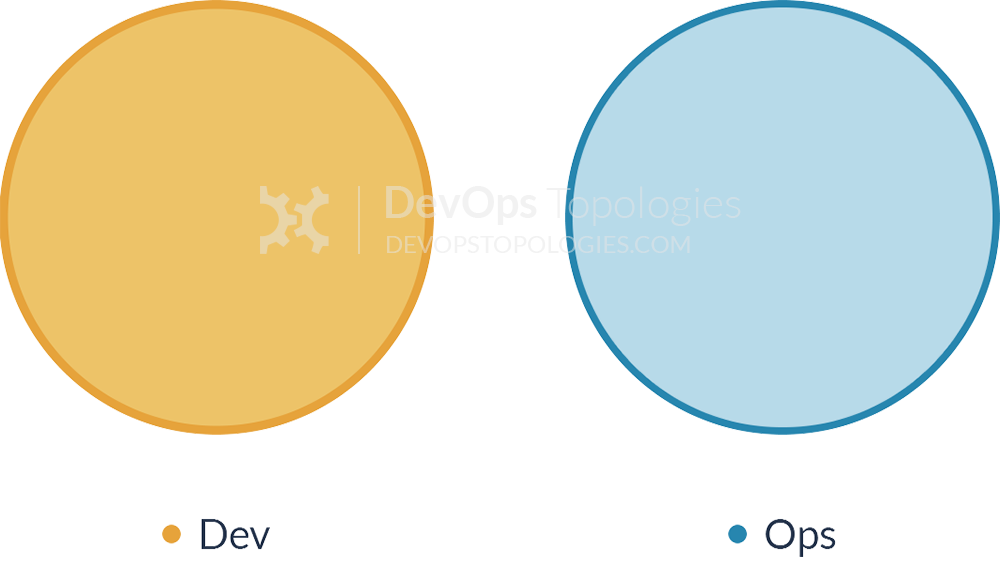

Anti-Pattern #1: Separate Silos

This one may seem pretty obvious as an anti-pattern, but many organizations that try to adopt DevOps try to do so without breaking down the barriers between the groups. The point of DevOps is to get everyone working together. It is hard to do that when team members are reporting to different departments, being measured on different criteria, and working towards different goals.

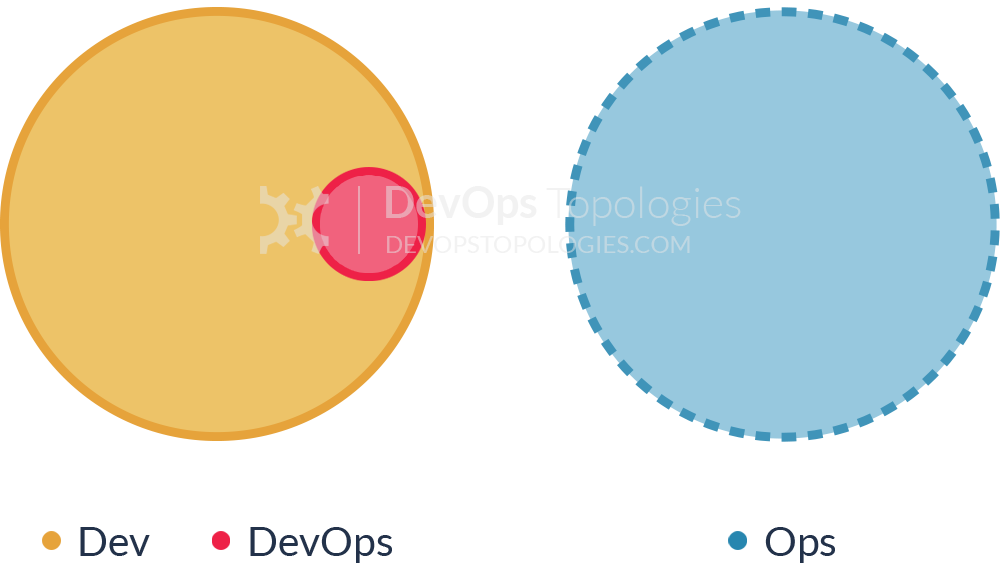

Anti-Pattern #2: NoOps

If the developers are handling DevOps, then we can get rid of Ops entirely, right? Obviously not. Getting rid of Operations entirely just means someone else (developers or testers) will be taking on their workload, only Ops probably isn’t something they are good at or familiar with. This is just a way to use DevOps as an excuse to cut head count.

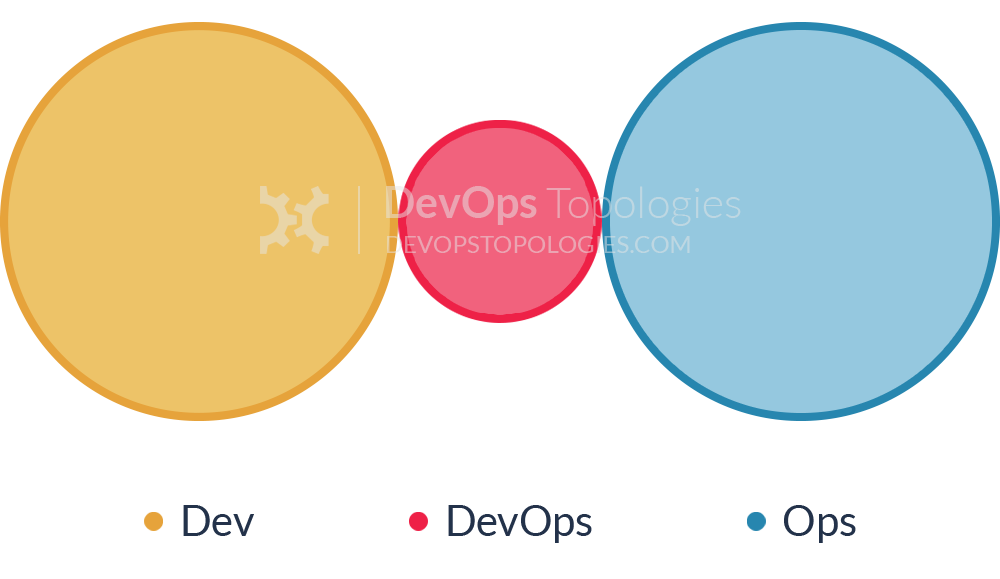

Anti-Pattern #3: Dev, Ops, and DevOps Silos

As DevOps is started up as a pilot program, a DevOps team forms to learn the new tools and technologies and then begin implementation. Then they become their own silo, making sure the uneducated masses don’t spoil their new utopia.

This is just one extra silo, and has all the same drawbacks with the addition of alienating other teams to the idea of DevOps.

This pattern can work, however, if it has a time limit. If the goal of the DevOps team is to make itself obsolete by bringing the other teams together then they can be effective as evangelists and coaches.

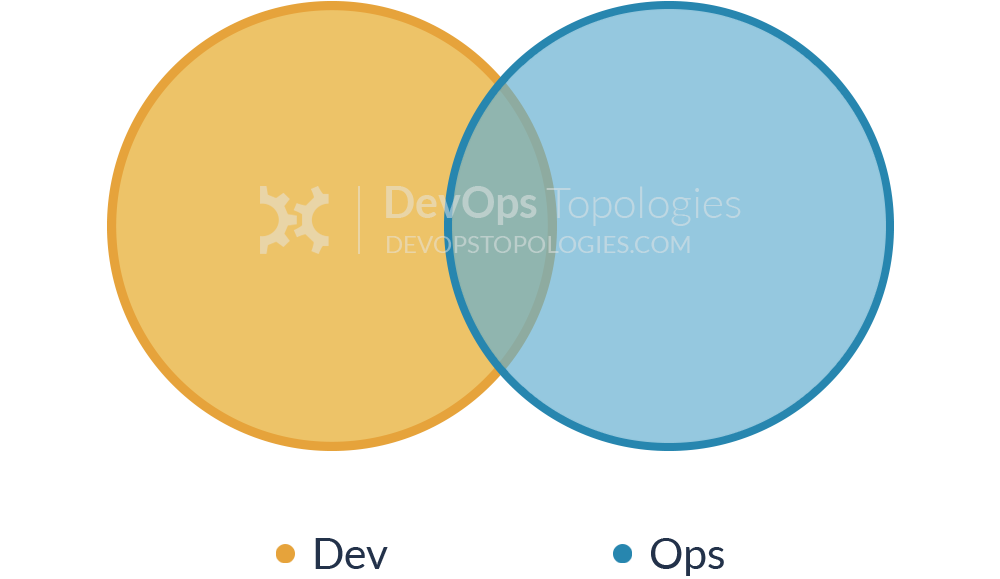

Structures that Work

The 2015 State of DevOps Report from Puppet Labs describes the characteristics of a “generative culture” that can succeed in implementing DevOps. Among the necessary traits are high cooperation through cross-functional teams, shared responsibilities, breaking down silos to encourage bridging.

So having teams that collaborate with some or significant levels of cooperation are the teams that will most likely succeed. By creating an organization where the team members can be co-located and work towards common goals with shared responsibilities, the teams can work effectively together to make sure the project is successful overall, not just focusing on the team members independent (and sometimes opposing) goals.

But this kind of cooperation doesn’t happen overnight. You need to get there somehow, and that probably means a transitional organizational structure. Typically, this will happen with some sort of pilot team that acts as the seed for the organization’s DevOps culture. As long as they don’t build themselves into their own silo, this team can become evangelists for DevOps, coaches and subject matter experts on the tools and processes, and possibly even a team of internal consultants that move from project to project guiding and leading other teams to DevOps success.

These DevOps teams need to be inclusive, bring other teams into the culture of DevOps and showing them by example how shared responsibilities and a collaborative culture helps the project and the organization as a whole. They have to work on sharing their knowledge and lessons learned. And they have to strive making themselves obsolete- eventually all teams show be embracing DevOps and their team is no longer needed.

There are several variations of this pattern- a DevOps team that acts as the conduit between the teams while bringing them closer together, a DevOps team that embeds themselves for some amount of time while coaching other team members, or a DevOps team that provides their expertise and advice as a service. In each case, however, the DevOps team has to be working to spread knowledge and make sure the teams take on the DevOps culture and processes for themselves.

Engineering Your DevOps Solution

Once DevOps starts gaining traction within the organization, the tools and processes to support it will become mission-critical software. Teams will begin to rely on the DevOps pipelines to deliver to production. At this point in the DevOps maturity, the tools and processes need to be built, maintained, and operated like a product. They will need 24×7 availability. Making changes in the pipeline to improve the processes or even just to update to tools to stay current will no longer be something that can be done whenever one team feels like it. Because if something breaks, all teams will be unable to deliver software.

The successful model we’ve seen is to develop a pipeline for your pipeline. Treat the tools and processes as a project, probably maintained by a team that can focus on the pipeline as a product. Separate the development and maintenance work being performed on the pipeline from the production pipelines being used by the other teams. Those teams cannot afford to be disrupted if anything goes wrong. And they will be focusing on their own software delivery, and may not be able to take advantage of the lesson learned and knowledge gained by other teams tuning and tweaking the pipeline for the needs of the individual teams and the organization overall.

Even if the pipelines are separately maintained for each team, there is a strong advantage to have one team that understands the pipeline tools, tracks upgrades, and sees how new tools can be added. Whether that information is rolled out as code, coaching, or a service to the teams consuming it, someone needs to be responsible for developing the DevOps pipeline itself and making sure it grows and matures.

Summary

Organization structure will drive team communication and goals due to Conway’s Law. Making sure the team members have common goals is critical to shared success, and therefore breaking down organizational silos is critical to DevOps success. You cannot have team members in a siloed organization try to work together without removing the barriers that keep their responsibilities separate.

A DevOps pilot team can work as a bridge between silos for a limited amount of time, as long as their focus is bringing the silos together and their long-term goal is making themselves unnecessary. But once DevOps has become mission critical, the tools and processes being developed and used must themselves be maintained and treated as a project, making a pipeline for your pipeline.

Further Reading

- “Conway’s Law.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 27 Mar. 2016. <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conway%27s_law>.

- Ashkenas, Ron. “Jack Welch’s Approach to Breaking Down Silos Still Works.” Harvard Business Review. N.p., 9 Sept. 2015. Web. 27 Mar. 2016. <https://hbr.org/2015/09/jack-welchs-approach-to-breaking-down-silos-still-works>.

- Skelton, Matthew. “DevOps Topologies.” DevOps Topologies. N.p., 2013. Web. 27 Mar. 2016. <http://web.devopstopologies.com/>.

- Waterhouse, Peter. “Why NoOps Is a DevOps Disaster Waiting to Happen – DevOps.com.” DevOps.com. DevOps.com, 01 Dec. 2015. Web. 27 Mar. 2016. <http://devops.com/2015/12/01/noops-devops-disaster-waiting-happen/>.

- “2015 State of DevOps Report.” Puppet Labs. PwC US, 2015. Web. 11 Nov. 2015. <https://puppetlabs.com/2015-devops-report>.

- Payne, Jeffery. “Why DevOps Engineering Is Important.” Coveros. Coveros, Inc., 23 Apr. 2015. Web. 27 Mar. 2016. <https://www.coveros.com/why-devops-engineering-is-important/>.